Preface

While Pope Paul VI's did not believe the street clashes leading to the killing

of a Catholic youth by Buddhist mob were signs of religious conflicts [New York Times, 1964], the

L'Osservatore Romano appealed to the South Vietnamese for calm in the midst of

further violence and protests after the ouster of President Diem's

First Republic.

While Pope Paul VI's did not believe the street clashes leading to the killing

of a Catholic youth by Buddhist mob were signs of religious conflicts [New York Times, 1964], the

L'Osservatore Romano appealed to the South Vietnamese for calm in the midst of

further violence and protests after the ouster of President Diem's

First Republic.

In the meanwhile, the U.S. bishops believed Major Dang's allegations and trial

were results of religious discriminations orchestrated by a pro-Buddhist

government to appease the raging turmoils threatening the new Military Junta's replacement.

Monsignor Asta, the Papal Delegate in South Vietnam, insisted on U.S.

intervention due to the indications that General Khanh's decision to attack

Major Dang Sy, at the trial, would precipitate an all-out religious war between

the Catholics and Buddhists [Blair, 1995]. U.S. Assistant Secretary of State, Mike

Forrestal, assured National Catholic Welfare Conference Legal Department, Harmon

Burns, that Premier Khanh pledged to reduce Major Dang's capital punishment and

would grant Major Dang the permission to leave Vietnam after the trial [United Nations Affairs, 1964].

This pledge was not fulfilled, as Major Dang was imprisoned, with no formal

charges, to Con Son Pennitary[New York Times, 1964]. The U.S. Catholics then ceased to convince the

U.S. government to intervene directly with Vietnamese affairs out of concerns

that further violence would be inflicted on the minority Catholics [United Nations Affairs, 1964].

References

1. Vatican Appeals for Saigon Calm. New York Times, 30 August 1964.

2. Poetic Justice in Vietnam? United Nations Affairs, 20 July 1964.

3. VIETNAM OFFICER DRAWS LIFE TERM; Convicted of Killing Eight. New York Times, 7

Jun 1964.

4. Blair, Anne E. Lodge in Vietnam: A Patriot Abroad. Yale University Press, 1995.

United Nations Fact Finding Mission

After the incident at Hue radio station, the arrests of dissidents at several Buddhist temples in Saigon, and the protest of Venerable Thich Quang Duc, Cambodia broke off diplomatic relation with South Vietnam and declined further U.S. aid packages. Laos declared neutrality. Sixteen members of United Nations filed human right violations against South Vietnam. To clear itself of the allegations of persecuting the Buddhists, the First Republic invited an independence panel of representatives to visit and did an exhaustive investigation of these allegations. Embassies from Afghanistan, Brazil, Costa Rica, Dahomey, Morocco, Ceylon and Nepal, accompanied by Marguerite Higgins, began their investigation on October 11 and concluded their findings on December 9, 1963. This report was largely ignored by international press until December 20, when Costa Rica Ambassador Fernando Volio-Jimenez granted an interview to NCWC News Agency and brought it to international attention.

On February 17, 1964, U.S. Senator Thomas Dodd (D-CT) presented these findings to Senator James Eastland (D-MS), chairman of U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Internal Security, to inform the American public that they had been misled [U.S. Senate Report, 1964]. On February 17, 1964, U.S. Senator Thomas Dodd (D-CT) presented these findings to Senator James Eastland (D-MS), chairman of U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Internal Security, to inform the American public that they had been misled [U.S. Senate Report, 1964].

During their visit, the fact finding mission was permit to travel anywhere in South Vietnam and met with many government officials, mainly Buddhists and Confucians, as well as members of the Buddhist Hierarchy. No Catholic clergies or citizens were invited to participate in the United Nations investigation.

Served as a time capsule, the mission's report consisted of United Nations recommendations, the testimonies of South Vietnam government officials, demands from moderate Buddhist leaders as well as the radical Thich Tri Quang accusations of religious persecutions.

The appendices included decrees, dated from Emperor Bao Dai's reign, stating:

1) All South Vietnam citizens could enjoy practicing their faith of choice.

2) All religious flags must be flown below the national flag.

3) Government could hold South Vietnam citizens indefinitely for political reasons.

Some of the findings included:

1) There were no religious persecutions as the law did not single out any one particular religion.

2) Deaths at the unfortunate incident near Hue radio station was caused by explosions, most probably made by Communist infiltrators. As South Vietnam army did not have such weapon in their possession.

3) There were only 8 dead, 7 children and one adult, in contrast to the 9 dead and 24 wounded, as perpetrated by the international press.

4) Victims suffered massive wounds, in contrast to claims of gun or artillery fires, as perpetrated by international press.

5) The victims came from various religions, not all were Buddhists, as perpetrated by international press.

6) A young Buddhist monk reported that he was recruited to perform self sacrifice acts, with promises of using drugs to dull pain, and he later learned the heinous acts committed by the government were complete fabrications.

Ambassador Volio-Jimenez stated that though no government was perfect, the very act of South Vietnam to invite United Nations investigators proved that the First Republic was forthright and willing to fix its human rights violations, as alleged by the sixteen member nations [U.N. Fact Finding Mission, 1963].

REFERENCES

1. United Nation Fact Finding Mission, 9 December 1963.

2. U.S. Senate Report to Subcommittee of Internal Security, 17 February 1964.

3. United States Congress, Biography - Thomas J. Dodd.

4. United States Congress, Biography - James O. Eastland.

The Trial

The trial, took place in Saigon on June 2, 1964 at 9:00 AM, with the presence of United Nations. It lasted for a week. The Military tribunal, or the Revolutionary Court, made up of eight military personnel, including General Dang Văn Quang and Colonel Dương Hiếu Nghĩa. The Honorable Lê Văn Thụ was the presiding Judge and Lt. Colonel Nguyễn Văn Đức was the Prosecutor. These were the same officials for cases against Ngô Đình Cẩn and Colonel Phan Quang Dong a year before, when both of the accusers were quickly judged and executed. Unlike the previous two cases which were held in Hue, the trial of Dang Sy was held in more orderly manner, the twenty families who represented the eight victims were absent [Hammer, 1987].

The charges brought against Major Dang were attempted and premeditated murders.

The prosecution sought the death penalty, if the defendant was found guilty.

Even though the incident took place at Hue, the prosecution and defense asked

the court to hold the trial in Saigon, away from the dissidents and possible

violence against the defendant and his family [Gettysburg Times, 1964].

The public reaction was frenzy. The Buddhists, initially demanded death penalty, proposed clemency if Major Dang admitted guilt. On the other hand, the Catholics demanded equal treatment for Major Dang, as other Buddhist perpetrators of the allegations [Times, 1964].

References:

1. Hammer, Ellen J. A Death in November. Penguin Publishing Group, 1987.

2. Start Trial For Murder. Gettysburg Times, 2 Jun 1964.

3. South Viet Nam: Again, the Buddhists. Times, 3 Jun 1964.

Allegations

While General Khanh's Revolutionary council released all Military Junta generals, he continued

to imprison Major Dang Sy. General Khanh was sure this move would improve his relation with

General Duong Van Minh's Military Junta while bolstering his support with

the militant Buddhists under Thich Tri Quang [CIA Weekly Report, 1964], [Moyar, 2006].

While in prison, Major Dang reported that he was pressured into pinning the

responsibility for the raising death toll on the only remaining Ngô figure,

Bishop Ngô Đình Thuc. He refused to do so, either in prison or at the trial

[Higgins, 1965], [Gheddo, 1970]. Had this ploy worked, the South Vietnamese Catholics and the Catholic

Church itself would have gone through an extremely difficult time [Gheddo, 1970].

References:

1. Higgins, Marguerite. Our Vietnam nightmare. Harper Row Publishing, 1965.

2. The Situation in Vietnam - CIA Weekly Report (June 1964)

3. Telegram From the Embassy in Vietnam to the Department of State, June 1964.

4. Dommen, Arthur J. The Indochinese experience of the French and the Americans: Nationalism and Communism in Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam . Indiana University Press, 2001.

5. Hammer, Ellen J. A Death in November. Penguin Publishing Group, 1987.

6. Gheddo, Piero. The Cross and the Bo De-tree: Catholics and Buddhists in Vietnam, (1970).

7. Moyar, Mark. Triumph Forsaken: the Vietnam war, 1954-1965. Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Testimony

To gain a neutral perspective, the First Republic invited United Nations to send

an investigative mission to South Vietnam, despite official protests from North

Vietnam. Even though South Vietnam was working toward membership in United

Nations, the Secretary General granted the request.

Completed in December 1963, this report had never seen the light of day since the media deemed it was unnecessary because the Diem government had been replaced [Higgins, 1965], [Hammer, 1987].

References:

1. Higgins, Marguerite. Our Vietnam nightmare. Harper Row Publishing, 1965.

2. Hammer, Ellen J. A Death in November. Penguin Publishing Group, 1987.

Verdict

While the First Republic government dismissed charges of misconducts and paid

indemptions to victims families in 1963, the Revolutionary Tribunal tried and pressed a

death sentence for Major Dang in 1964 [Gadsden Times, 1964].

Major Dang, maintained his and his men's innocence in the cause of deaths. Fifty

men were released but the sentence still progressed toward extreme penalty for

Major Dang.

The victims of the blasts came from mixed backgrounds and religions. While the

media reported the victims were Buddhists, they glossed over the fact that at

least one of the victims was a Catholic [New York Times, 1964]. The cause of the blasts were of

unknown origin, even until today. Major Dang, while escaped harm, was implicated

because of the his vincinity to the casualties. Post-mortem autopsy, performed

by Dr. Le Khac Quyen, revealed the corpses were damaged by explosion, not

ammunition. MK3 concussion grenades used by Major Dang's troops were determined

to be non-lethal. Dr. Wulff's testimony and medical office corroborated that

victims were killed by larger, lethal explosions.

Despite the prosecution's press for the death penalty, Major Dang's lawyer

contended that the court could not establish concrete evidence to prove beyond

reasonable doubts of his client's alleged crimes. Major Dang concluded his

defense by saying he was a victim of a religious conflict [Gadsden Times, 1964].

When the military tribunal pronounced sentence, sympathetic Catholics and

Buddhists lined the streets in protest in the following Monday, prompting many

international observers to speculate an internal civil war was about to be

erupted [Gadsden Times, 1964], [ Keesing's World News, 1964], [Topmiller, 2006].

References:

1. Death Sentence Asked for Vietnamese Major. Gadsden Times, June 6, 1964.

2. Religious-political Furor In Viet Nam Sparks Noisy March. Gadsden Times, June

8, 1964

3. VIETNAM OFFICER DRAWS LIFE TERM; Convicted of Killing Eight. New York Times,

June 7, 1964

4. Protest Against Military Rule, 100,000 marched. Keesing's World News, December 1,

1964 .

5. U.S. Senate Report - POW and MIA. Government Printing Office. 1992.

6. Topmiller, Robert. The Lotus Unleashed: The Buddhist Peace Movement in South Vietnam, 1964-1966. University Press of Kentucky, 2006.

7. Life Term for Officer in Viet Row.

Gadsden Times, June 8, 1964

Further Turmoil

Tension between Catholics and Buddhists over the life sentence given to Major

Dang Sy heightened [New York News, 1964].

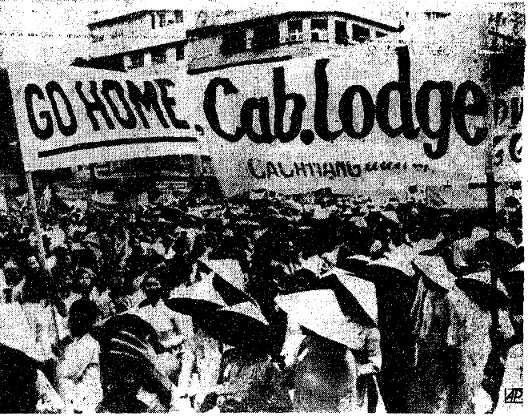

On Monday, August 9, 1964, 40,000 people marched across Saigon and surrounding

areas protesting the sentencing as well as the odd silence of the United States.

Crowds carried English banners urging U.S. Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge to state

his official stand and demanded the Revolutionary Council's stand on governing South

Vietnam. As the crowds converged at the Cathedral in Saigon, some even tried to

tear down the memorial plaque for the late President John F. Kennedy, saying

religious ground was not a place for politicians. Though they were promptly

stopped by others in the crowd, most South Vietnamese felt the Kennedy

administration was partly responsible for the death of President Diem [New York News, 1964]. Some believed that

Ambassador Lodge was molding the subservient Nguyen Khanh's government which was held under the sway of

certain Buddhist leadership influence [Associated Press, 1964], [Blair, 1995].

On the following Wednesday August 11, 1964, a petition, signed by 345 Catholic

clergies, was delivered to General Khanh Nguyen asking clemency for Major Dang.

The petition stated the charges were vague and the conviction was based on the

testimonies of two men who changed their stories and contradicted each other.

General Khanh stated that he would open a commission to review Major Dang's

case [New York News, 1964].

South Vietnamese army went through a period of demoralization as commanding

officers refused to execute orders from their superiors without written

authorization. They blamed the frequent replacement of their superiors would

make them doing their duty one day and be punished by the next incoming

commanders. They did not want to go through the same ordeal as Major Dang Sy [The Daily News, 1964].

The United States silence on the trial of Dang Sy had created a double standard.

As the media and U.S. government condemmed Saigon regime on Buddhist

persecution, little or no coverage on the arrests of Catholic military

personnel. Father Patrick O'Connor observed that Buddhists or those claimed to

be of this faith, were given preferential treatment, even in cases of committing

crimes [New York News, 1964].

References:

1. New Religious Tension Builds. New York News, August 9, 1964.

2. Vietnamese Catholics Rap Lodge. Associated Press, August 9, 1964.

3. Douglass, James. JFK and the unspeakable: Why He Died and Why It Matters. Orbis Books, 2008.

4. Saigon Frees 9 Diem Aids. New York News, October 19, 1964.

5. U.S. Must Correct Vietnam Errors. The Daily Reviews - June 25, 1964.

6. Vietnamese Can't Figure U.S. Stand on Riot Against Government. New York

News, September 9, 1964.

7. Blair, Anne E. Lodge in Vietnam: A Patriot Abroad. Yale University Press, 1995.

Aftermath

While the initial reports from U.S. Embassy and Halberstam-Sheehan in Saigon

reported that Major Dang ordered troops to fire on peaceful demonstrators, or

the victims died from grenades on the radio station's balcony; subsequent

U.S. State Department reports restated that Major Dang's troops were not involved in the casualties at

the Hue radio station and the deaths were caused by large, unknown explosions.

They further elaborated that the death tolls were limited to 8, instead of 9

with many wounded, as stated in the initial reports. According to a CIA high

level official, George Carver, the source of the explosion would probably remain

a mystery, shrouded in secrecy, for all times [Hammer, 1987].

In a report to the U.S. Congress Subcommittee of Internal Security, Senator

Thomas J. Dodd presented the false reports created about South Vietnam. He

informed the subcommitee that the United States had been misled by radical

reporting that led to the ouster of President Diem [Dodd, 1964]. In his testimony to

Congress, CIA director William Colby also expressed his doubts in the reports of

Buddhist persecutions. He iterated that Major Dang Sy did not order his troops

to open fire on demonstrators, though actions taken by the South Vietnamese

military were witnessed by German doctors [Prados, 2004]. In Congressional Recording Volume

114, the U.S. Congress found that Major Dang Sy was a 7 times decorated hero in

the South Vietnamese Army and was held without formal charges. The Trial of Dang

Sy had created such financial burden on the Dang family that several U.S.

faith-based charities had to provide financial support to Mrs. Dang [HR 12449, 89-2, 1966], [Congressional Recording, 1967].

One of the presiding members of the Military Tribunal, and Major Dang's lawyer

contended that the court sentenced Major Dang without proving beyond reason of a

doubt, based on inconclusive and unconnected evidences. This was done to court

the radical Buddhist movement for supporting a fading Military Junta that was

facing further turmoils [Hammer, 1987]. The most notable act that caused violence under

General Khanh's regime was the revised Vietnamese Constitution (Vietnamese: Vũng

Tàu Hiến Chương).

The plight of Major Sy Dang came to the attention of Mrs. Anne Westrick in 1966

who petitioned to U.S. Congress, Departments of Defense and State, and allies

government for Major Dang's freedom [Owosso Argus-Press, 1966]. General Khanh's Military Junta was

replaced in 1967 by Premier Nguyễn Van Thieu. The Second Republic, called for

unity in South Vietnam and promised to a better government and future for South

Vietnam [Christian Science Monitor, 1967], offered Major Dang a choice of returning to his rank or resigning to

the life of a civilian. Major Dang chose the latter. A member of Vietnamese

Congress then introduced Mr. Dang to an office of Bank of America in Saigon,

which offered Mr. Dang employment [Baltimore Sun, 1987].

In 1970, the Hoa Binh newspaper ran a story that Captain James Scott, who was

reassigned to Mekong Delta region, admited that he was the one who set the

explosive devices [Hammer, 1987].

As for the cause of deaths for the eight victims, the debates raged on, even

until today [Wolf, 2002], [Truong, 2010].

References:

Dodd, Thomas. Testimony to U.S. Congress Subcommitee of Internal Security, 1964.

Hammer, Ellen J. A Death in November. Penguin Publishing Group, 1987.

Happy July 4th. The Baltimore Sun, July 1987.

Prados, John. Lost Crusader: the Secret Wars of CIA director William Colby. Oxford University Press, 2004.

Nine Diem Backers Released. New York Times, October 1966.

State Woman Fights for Major's Freedom. Owosso Argus-Press, March 1966.

Thieu Voices Appeal for Unity and Sacrifice. Christian Science Monitor, November 1967.

Truong, Vinh. Vietnam War: The New Legion. Trafford Publishing, 2010.

United States Congress: House Committee on Foreign Affairs - Foreign Assistance Act of 1966, H.R. 12449, 89-2.

United States Congressional Recording Volume 114. Government Printing Office (1967).

Wolf, Marvin J. and Nguyen, Cao Ky. Buddha's Child: My Fight to Save Vietnam. Macmillan Publishing, 2002.

|